|

|

Musicians using buckets and calabashes instead of drums |

Evans Akangyelewon Atuick

The Tradition and Change in the Bulsa Marriage Process: A Qualitative Study

INTRODUCTION

Marriage is very essential for the survival of every society since it allows for procreation and the upbringing and socialization of the young ones in the acceptable normative behavioral patterns of life in a particular society. Just like any other African society, the Bulsa see marriage not just as a union between partners (usually a man and a woman) but as a union between the family of the man and that of the woman who are getting married. This is because following the conclusion of the marriage process, both families become unified as one and join or assist each other in the performance of socio-cultural events such as pouring of libation (in some cases), joyous occasions and even funerals among others. This paper is based on the premise that the Bulsa marriage process has undergone some changes or has been encroached upon by foreign marriage forms with far reaching implications for the customs and traditions of the Bulsa.

As far as the Bulsa are concerned, a woman is invaluable, hence, no price can be put on her head for marriage. This belief is encapsulated in the proverb, ”nipouk ka fogli” – this literally means ‘no woman is useless or chaff’. As a result, courting and marrying a Bulsa lady involves a simple process that does not necessarily involve huge expenditure. This is completely different from the marriage processes of neighbouring tribes such as the Kassena, Nankam and Frafra which usually involve payment of several cattle, sheep and guinea fowls. In the wisdom of our forefathers, the simplicity of the Bulsa marriage process ensures two things; firstly, that young men desirous of marriage can easily do so and start a family without difficulty, and secondly, that our women, when they do eventually marry, are accorded the necessary respect and cannot be mistreated since the husband did not “buy” her from her paternal home.

This paper therefore looks at the traditional marriage process among the Bulsa by, first and foremost, examining the process in its pure state, and then discussing the changes and developments that have taken place over time and their implications. Data for this paper was gathered from five experienced men and two women, between 65 to 80 years, who are well-versed in the customs and traditions of the Bulsa through an in-depth guided interview. I have also used experiences I have acquired as a participant observer in a number of marriages, where, I played the role of ‘link-man’ (san-yigma).

THE TRADITIONAL MARRIAGE PROCESS

The Bulsa marriage process takes place in three main phases namely dueeni-deka (‘courtship/knocking phase’), akaayaali-ali-wa-boro (‘blocking of any other suitors from proposing to the lady’) and nansiung-lika (‘closing of the gate or entrance’). There is a fourth phase, zangi-bobka (‘tying of the wooden pillar’), but this is only performed during the funeral of the actual father or mother of one’s wife. I shall now take these phases one by one and discuss them.

Dueeni-deka

The marriage process usually starts with the knocking phase whereby a young man meets the prospective bride and expresses interest in her. They then meet a number of times usually at public occasions such as market, festivals, funerals as well as other places outside the home. All this while, the two are forbidden from engaging in sexual intercourse until they are duly married. When the young man eventually becomes convinced that this is the sort of young woman he wants as a wife, he informs her of his intention to visit her paternal house in order to know where she lives and to know her parents. Following this, the prospective groom, in the accompany of a friend or two, proceeds to the compound where the prospective bride hails from. On getting there, they would merely greet the landlord/father and then enter the compound, eventually ending up in the douk (‘room’ or ‘household’) of the mother of the young woman being courted. They, first of all, greet the mother of the young woman and then tell her that they have a vaanchoa (‘companion’) in this house and therefore came to see where she lives and to meet her people. The mother would accept the greetings and may offer zom-nyiam (‘millet/sorghum flour water’) or ordinary water to the visitors. If any of these is provided, the actual suitor is forbidden from drinking that water but the friend(s) can drink and return the calabash to the woman. After this, the suitors would ask for permission to leave for home with the assurance that they would return on another day. It is important to point out that, on this first visit, the suitor is not obliged to give anything to either the mother or father of the prospective bride.

However, on the subsequent visit to the house, the suitor can greet the father with goora (‘cola-nuts’) before proceeding to see the mother. All this while, they would not discuss their plans with the landlord or father of the lady but deal with the mother only. The suitor and his friends then greet the mother and tell her that their companionship with her daughter has reached a stage where they want to formalize it and are therefore here to formally greet her and to let her know that they are interested in her daughter. Having said this, they proceed to give her whatever they have brought with them, usually goora and money (white cowries, togfa (‘shillings’) or kobouk (‘pesewa’). If the mother is impressed, she will call the young woman in question to come and see them while she makes arrangements to provide something for them to drink or eat. Once again, the actual suitor of the daughter must not eat or drink anything offered but the friends can. Once the young woman comes in, the suitors must also give their prospective bride some money as a way of not only showing their love for her but also wooing her to their side. As it is permissible for a young girl to have a number of suitors all coming and wanting her hand in marriage, it is the mother’s duty to find out which of the suitors she actually loves and wants to follow home. She must also inform her father that some suitors have shown their intent to marry his daughter. It is important to note that at this stage of courtship, the mother of the prospective bride is very important and has great influence on her daughter’s choice of marriage partner. As a suitor, you ought to win the mother of the lady to your side by any possible means and once you did that very well, you stood a great chance of whisking the lady away to the comfort of your house. Moreover, the number of visits a suitor makes to the house of his prospective bride before she agrees to follow him home depends on how well the mother is wooed and whether the lady loves a particular suitor.

It is also important to point out the fact that a suitor is forbidden from marrying a young woman if he comes across certain activities being done in the compound of his prospective wife on a visit. Therefore, on any visit, a serious suitor must make sure that he and his friends do not arrive at the compound at a time someone is engaged in making Bulsa-kpaam (‘sheabutter’) or tiak-peka (weaving a local mat made of elephant grass - Pennisetum purpureum), for seeing these would be a sign of bad luck and a sure sign that the young woman was not your God-given wife. According to Bulsa custom and traditions, any woman who marries under such circumstances is more likely not to bear children for the man and would not even stay in the compound of the would-be-husband for a prolonged period without difficulty; she would either die, fall sick or depart. In the past, the belief was so strong that any suitor who unfortunately visited a compound of a prospective wife at any time or day and met either of these activities being carried out, would simply depart and abandon his interest in that particular young woman. As a result, it became normal practice for a suitor to find a woman from his area who has married into the neighbourhood of his would-be-wife or a friend to make checks and inform him when it was clear to visit the compound of a would-be-wife. Therefore, on visits to the compound, the suitor would make a stopover at the house of his relation or friend and wait for them to spy on the compound and give him the green light before he proceeds to the compound.

Barring any such unfortunate events, on a particular visit by the suitor, the lady could give the suitor a particular day to come and they would go home together, provided she is equally interested in marrying him. The suitor and his friends must go and come back on the appointed day as if they were not aware of any such plans and go through the necessary customary greetings and the usual gift giving without leaving any hint of their plans with the lady. The lady would then tell them to wait on her at a particular place on leaving the compound. After greeting and completing the usual formalities with the mother and father, the suitor and his friends would bid farewell and proceed to a meeting spot revealed to them by the lady. In the meantime the young woman would sneak out of the compound, usually by scaling a wall or by any other means possible. She then joins the chosen suitor at the waiting point and together they proceed to the suitor’s compound where they do the akuwaaliba (singing and merrymaking to announce to the world the taking of a wife by the young man). Once the akuwaaliba is completed, the lady is deemed virtually married to the young man and it becomes a taboo for anybody from that area or distant male relations of the new bridegroom to seek her hand in marriage in the event that she ever quits the marriage and returns to her paternal home.

At this juncture, it is important to shed light on the akuwaaliba, which is usually done late evening until the next day. However, wealthy or relatively well-to-do families can get the local musicians to sing and dance for three or more days. Usually local musicians are recruited to come and perform the akuwaaliba once the suitor is sure the would-be-bride is coming home with him on a particular day. On the appointed day, the musicians arrive at the compound of the groom around 7-8 pm and once the couple arrive, they meet them outside the entrance to the compound and break into the chorus of the akuwaaliba:

Waa akuwaaliba eeei!!

The suitors who were roaming at night and searching

Should stop wasting their time because

A. (here they mention the basein -‘praise name’- of the suitor, e. g “Asalipiung”, the powerful one who leans against the rock) has finally arrived.

Oh yes, A(salipiung) has finally arrived,

And has taken his possession.

It is all over because A(salipiung) has finally arrived;

And arrived well.

All other rivals should stop searching.

Waa akuwaaliba eeei!!

All other suitors should stop roaming at night.

It is all over because A(salipiung) has beaten them to it.

While this is being done, the landlord or head of house (yeri-nyono) would ask to know why they are making noise in his compound at that hour of the day. They would then stop the singing and inform him that a young man from his compound (name of groom) has just taken a new wife, hence, they are bringing the new bride home. The yeri-nyono, upon hearing this, would give them permission to enter the house and if he is wealthy or powerful, he could kill an animal (sheep, goat or cow) and place it at the entrance for the bride to pass over that animal and enter the compound. This killing of the animal is symbolically an expression of joy, a way of showing that the compound is wealthy enough to be able to take care of the new bride and above all, a way of blessing the new bride to be fruitful.

|

|

Musicians using buckets and calabashes instead of drums |

However, this practice is not obligatory to all but the preserve of the mighty and wealthy family heads. Once the landlord grants permission for them to enter his compound, the musicians continue with the akuwaaliba chorus until they arrive in the Ama-douk (‘mother’s room or section within the compound, usually where the great grandfather/mother or grandfather/mother of the groom once lived’) where they climb onto the room of the gbong (‘round room with stairs and roofed with sticks and mud, creating a flat roof-top resting place’) and continue with the singing. The new bride is, however, given a mat to sit on the floor of the courtyard of the douk, flanked by young women or men of the house in order to make her comfortable. After the singing has gone on for some time, the landlord would come in with one or two fowls, a guinea fowl and some refreshment. He would ask the singers to stop singing and listen to him. He would then express his joy at having a new addition to his compound in the form of a wife and also for having the musicians with them to entertain and make merry with them; he would then pray to his fore-fathers for a fruitful and blissful marriage and also for the protection of all who have come to the compound to join them to welcome the new bride. After saying this, he will just hit the fowl on the ground and throw it onto the roof top for the yi-yiilisa (‘musicians’) while the guinea fowl is given to them to prepare something for the new bride to eat following

|

|

Dancing and merrymaking |

her long and tiresome journey to the compound. He is also expected to give another fowl to friends of his son who helped in bringing the new bride to th

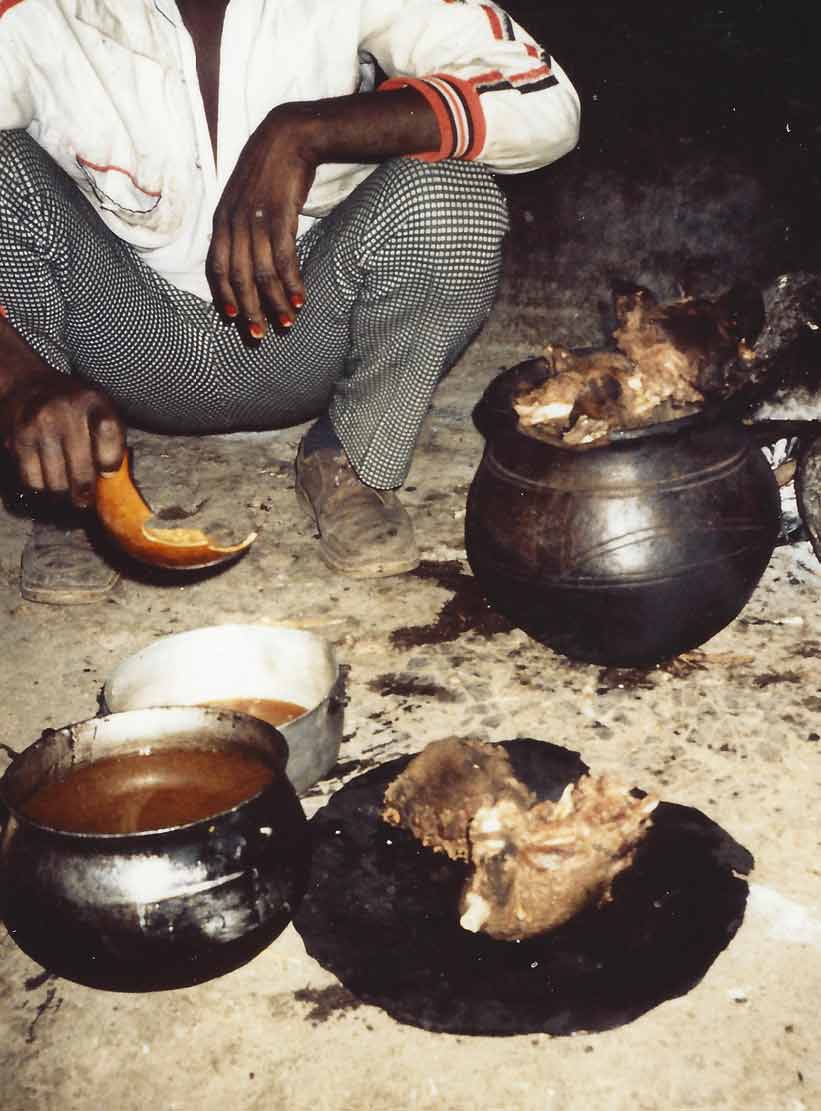

e compound but this is not obligatory. The singers must also be given some ‘water’- (da-monung, ‘pito’) or zom-nyiam (‘millet/sorghum flour water’) - when foreign drinks are not available, and nowadays, akpeteshie (alcoholic drink) - to motivate and strengthen them to be able to perform well. After taking the refreshment, the singers would descend from the gbong and prepare their musical instruments (usually calabashes stocked with racks, metal buckets etc.) to begin the jong-naka (making of entertaining and danceable calabash music).

Meanwhile, the fowl for the singers would be de-feathered and the feathers scattered all over the floor for the new bride to clean it the next day as a sign of her readiness to take care of the house. Thereafter, there is drumming, singing and dancing throughout the night until the morning when the landlord shall come again to kill another fowl for them and bid the singers farewell.

Akaayaali-Ali-Wa-Boro

|

|

Presenting the dog for the "brothers" |

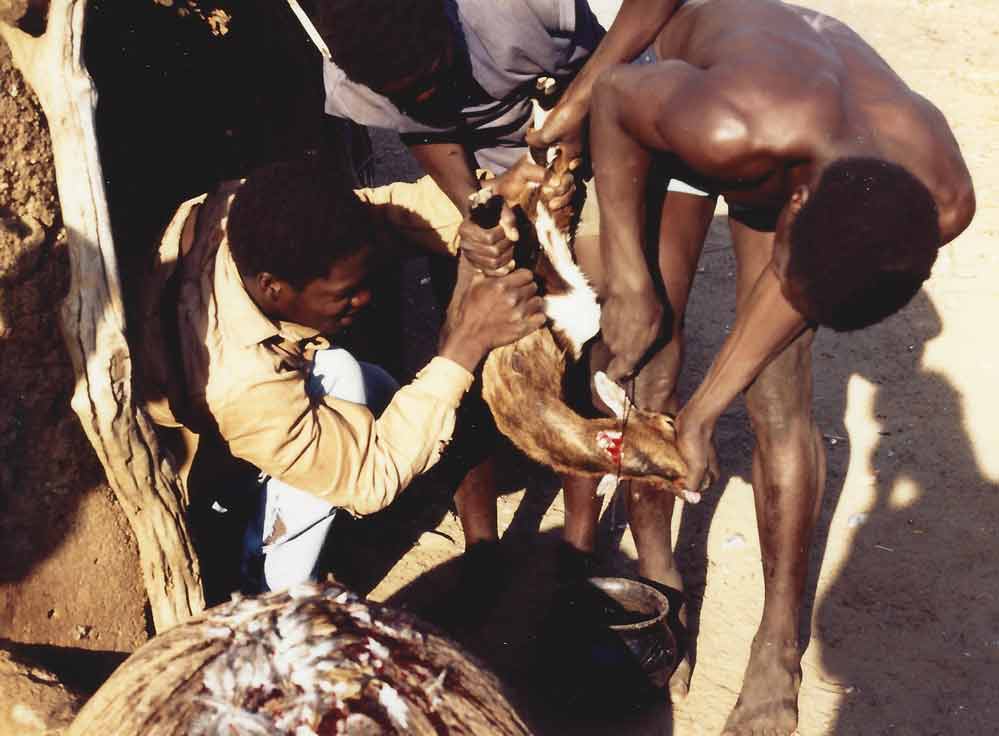

A day or two after the akuwaaliba, the young man (groom), in the company of a friend or two, must return to the compound of the bride to formally inform her father that they should stop looking for her because she is with them and that they are willing and ready to formalize their union. The father of the young woman would then tell them everything they needed to know as to what to do to formalize the marriage. Having officially informed the landlord and heard what is demanded from them, the young man and his friend(s) would bid him farewell and depart for home. Following their return to their compound, the brothers of the bride will follow up to the compound of their sister’s husband for the poi-deka (‘eating of the womb’) whereby there is the symbolic killing of an animal (either a dog a sheep or goat) for the brothers who must eat everything with the exception of the waist, which must be handed over to the head of the girl’s family upon their return home. This actually confirms that their sister or daughter is actually married and that her brothers have been treated well by her husband and his family.

After the poi-deka, the family must recruit a san-yigma (‘the link-man’), usually a man whose mother or

|

|

The dog prepared |

grandmother hails from the community of the bride or a nearby community, who performs the actual marriage rites on behalf of the groom. Once a san-yigma is found, they provide him with all the necessary items for the “akaayaali-ali-wa-boro” for him to proceed to the compound of the lady to initiate the rites.

The items for this rite vary from place to place; in some areas they collect goora (cola-nuts), tabi (‘tobacco’) and money - kuboata pisinu (‘50 pesewas’) while in other places they collect only goora and money - kuboata-pisinu. The san-yigma on getting to the area where the woman hails from, would usually find the san-yigdiak (a man who has relations with the place of origin of the groom, especially one whose mother hails from that area or an area close to that area) to assist him to perform the rites. The two of them then proceed to the bride’s paternal compound and hand over the items required after going through the necessary customary greetings and formalities. The acceptance of these items virtually signifies that the family of the woman have accepted and formally given her hand in marriage to the man on whose behalf the san-yigma and san-yigdiak have come to greet and offer the items. It also means that another man cannot come to seek the lady’s hand in marriage since the family is now aware of her marriage to that particular man. Once the items have been accepted, the san-yigma must return to tell the groom and his family what transpired over there and what else is expected of them.

Nansiung-lika

|

|

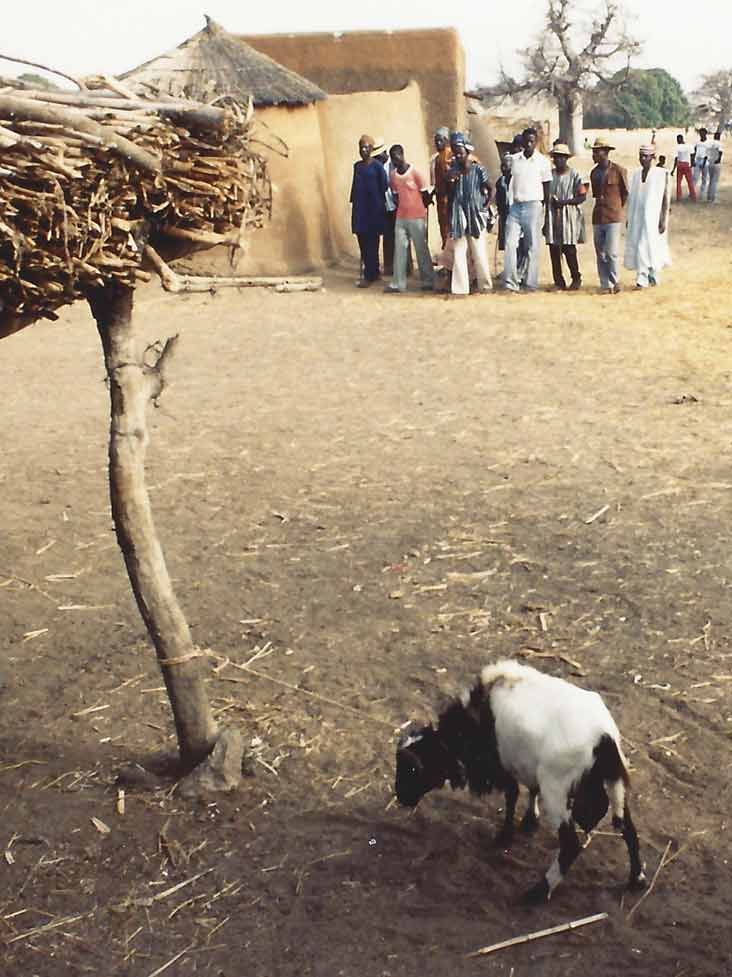

The nansiung-lika goat being killed and sacrificed |

This is the last and most important phase of the marriage process because it symbolizes the closing of the gate, hence, the woman becomes his [the man’s] wife forever until death separates them. It also means that the man has completed all rites required of him to formally own the woman and any children that may be born out of that marriage. As a precautionary, most people do not perform this marriage rite until they are sure the woman is productive and willing to stay with the man forever. The normal practice is to allow the woman to deliver a number of children before going ahead to perform this particular rite. It is, however, a taboo to perform this rite while the woman in question is pregnant because it is believed that it will have negative repercussions on her health and the outcome of the pregnancy.

The nansuing-lika (closing of the entrance) is again done by the san-yigma with the assistance of the san-yigdiak. The items for this particular rite vary in terms of time and from place to place. With regards to time, if the rite was to be performed before the woman gave birth, then the most important items are goora (cola)

|

|

Tobacco and a hoe blade, part of the nansiung gifts, are stored under the roof |

and kpiak (a hen), but in some places they accept kunkuri (a hoe) in addition to the goora and kpiak. However, once the lady in question has given birth, “posuk” (a sheep] is demanded in place of the kpiak. The rite varies from place to place because in some places they accept the goora, kpiak and posuk collectively; in other places they may accept goora, kunkuri and kpiak or posuk as the case may be; and in other places, they accept only the posuk and any other gift one may have including goora, drink etc. Once the san-yigma is sure which of the named items are being demanded by the house of the woman, he collects them from the husband or his father and proceeds to the woman’s paternal compound in the company of the san-yigdiak to perform the rite. On getting there, they will meet the men of the compound in the kusung (hut) outside the compound and complete all the necessary customary greetings and then tell them their mission. They then hand over the cola and the sheep or hen and any other thing they have with them to the elders of the compound. The elders would normally accept them and ask them to enter the compound for some refreshment. The acceptance of the items brings to an end the nansuing-lika rite and the formal completion of the marriage process.

|

|

Zangi-bobka |

The “Zangi-bobka”

This is only done when the final funeral rites of the actual father or mother of one’s wife is being performed. During such an occasion, the husband of their daughter, led by his san-yigma, must bring a healthy-looking live animal, preferably a sheep, and tie it to a pillar of the local hut or somewhere in the nankpieng (main courtyard of the compound that sometimes had a double function as a kraal for family livestock). This symbolizes the huge loss the husband has incurred following the death of the in-law as well as a show of respect for the departed soul, who was a strong pillar in his marriage life.

CHANGES AND DEVELOPMENTS

This section will be examined from two perspectives, namely actual changes in the traditional marriage process, and new types of marriage unions and their implications. I would start by examining the changes in the traditional marriage process and then zero in on the new marriage forms.

Changes in the Traditional Process

These changes have occurred in various forms such as the introduction of new items, the truncation in the process as well as changes in the key persons involved. Regarding the introduction of new items, alcoholic drinks such as dry gin, schnapps and akpeteshie [locally brewed gin] were originally not part of the core items required for marriage but have over the years been regarded as such. Another new item that is nowadays demanded is gatiak (‘cloth’). It signifies the cloth on which the lady was born and taken care of until maturity and this is usually converted into money. In two out of the three marriages that the writer was involved in as a link-man, the gatiak was demanded by the youth and it was given in the form of money ranging from Ghc 50 to 100. Another worrying trend is the incessant demand for money by the elders of some areas during some visits of the suitor. For instance, in all three marriages that the writer was personally involved in, money was given out to the elders and even the youth but they kept complaining that it was small and more had to be added. In the opinion of this writer, this act of bargaining for more money by the youth and elders was overstretched. It is, however, important to point out that all three individual suitors were not natives, hence, that could have played a part in the unnecessary demand for money by the families of their prospective brides. Moreover, some minimal level of heckling of and/or bargaining (in some cases with the exception of the core items for the akaayaali-ali-wa-boro and nansuing-lika rites) with the groom or his representatives by the family members of the bride is usually customarily allowed in order for the latter, who are losing their daughter or sister to the former for good, to get more benefits in return. However, these must not be overstretched and should usually cease as soon as the groom or his representatives add a little of a particular gift or money. For instance, in the course of the ‘poi-deka’ or ‘dueeni-deka’, the brothers or elders of the would-be-bride’s family can bargain in terms of the size of animal to be killed or the quantity or quality of a particular gift; the groom or his representatives would usually respond by getting a bigger animal or adding more of a particular gift or some money to compensate for the shortfall. Heckling could also take several forms such as the brothers seizing their ‘sister’ and preventing her from leaving with the would-be-groom; brothers were blocking the main entrance and preventing the would-be-groom or his representatives from entering or leaving the compound or elders pretending not to know that their daughter is dating a particular suitor, hence, they were not willing to accept anything in respect of the rites of marriage. However, this is usually amicably resolved after the groom or representatives agree to give something to appease the would-be- in-laws.

The marriage process has been truncated to the extent that some people are now allowed to carry out all three phases in one day. This was the case in all three marriages the writer was involved in. A detailed analysis of one of such cases would suffice.

Case 1: The

father of this young woman was a very powerful man based in the city. He had

already called home to instruct the elders to allow for one day all-in-one package. The young

man interested in marrying this man’s daughter was an Ewe. The writer received a phone call

from this man (the would-be father-in-law of the suitor), who asked the writer to lead the would-be couple to his paternal compound as san-yigma (link-man). The first reaction of the writer was

that of a shock because by custom, the writer was considered a ‘brother’ of his daughter based on

place of origin and also, the writer was not in any way related to this Ewe suitor, hence, not

actually qualified to act as his san-yigma. Reluctantly, the writer agreed and proceeded to his

residence where they were waiting for him. On getting there, he asked to see what they had

brought and was shown three marked envelopes (labelled elders, brothers and mother) with

money, a fowl, sheep, hoe, tobacco, cola and bottles of dry gin. Straight away, he told the mother

of the young woman that once she had not delivered, the big ram was not necessary but she

insisted we took it along, otherwise the suitor would think he got her daughter cheap!! We

proceeded to the compound, where we left all the other items in the vehicle with the exception of

the items for the knocking, namely some cola, the marked envelopes and bottles of dry gin. We

greeted the elders and handed over the cola, four bottles of dry gin and two envelopes marked

“elders” and “brothers”. The writer then sought for permission to enter the compound and it was

granted. Inside, we greeted the eldest woman (in the presence of other women in the compound),

told her our mission and handed over the cola, the marked envelope and two bottles of dry gin. We

had to give an extra Ghc 10.00 after the old lady complained (part of the normal heckling and

bargaining) that the weight of our envelope did not match up with the beauty of their ‘daughter’,

hence, we needed to do more to be able to take their daughter away. Knocking was done!! They

prepared zom-nyiam (millet or sorghum flour in water) for us, but the writer was the only one

who took it. We bid them farewell and went out to the hut where the elders and youth were

waiting. Straight away, the young men demanded their poi-deka (‘eating of the womb’) and we

had to convert this into money since the suitor did not prepare for it. Eventually, the suitor gave

the writer a hundred Ghana cedis to take care of it. Ordinarily, the brothers of the girls would

have had to visit Eweland for their animal but if they could get it right there, why not? They also

demanded the gatiak (‘cloth’) and were given Ghc 80.00. All this while, the young woman was

still indoors and once she emerged the young men grabbed her and began preventing her from

entering the vehicle. It meant that we had to pay for her release and ended up parting with

another Ghc 30.00 before she was allowed into the car. At a distant from the compound, the car

parked and the writer got down with the items for the akaayaa-ali-wa-boro namely, the cola,

tobacco and 5 cedis to represent the kuboata-pisinu (‘50 pesewas’). He proceeded to the hut

where the elders were waiting for him; he greeted them and handed over the cola, tobacco and

the Ghc 5.00 (in place of the 50 pesewas) as custom demanded. When these were accepted, he

excused them and left only to return with the items for the nansuing-lika: the cola, hoe, and hen,

as well as the ram. He again exchanged all the necessary customary greetings as if he had come

on another day before handing over the cola, hoe and hen. When these were accepted, he told

them that the young man was so happy that they had given their daughter to him that he gave the

ram as a gift to them. It was accepted and he thanked them and left. The marriage rites were duly

concluded in record time!!!

Case two was done the same way, but case three was quite different in that tobacco was not required for the akaayaali-ali-wa-boro; only cola and Ghc 2.00 were required. Moreover, the ‘yeri-nyono’ (head of compound) resisted all attempts to allow any rites to be performed until he had seen his daughter to be sure she was really interested in the marriage proposal; in the end only the “knocking” was done. Apparently, the actual father of the lady was aware of the young man but the yeri-nyono had never been aware that their daughter who was studying in Tamale had been dating a young man from Chiana (Kassena area). This landlord certainly knew the custom and what was expected of him.

The change in people involved and even in the items is more common among Bulsa in the Diaspora. Previously, only people who had maternal relations with a particular family, lineage or village were qualified to lead the marriage rites as san-yigma but not nowadays. Anybody, including relatives of the woman can perform that role as illustrated in the role the writer played in case 1, 2 and 3. It is also not uncommon for a young woman or man getting into marriage in the city to just arrange for any elderly Bulsa, who may not even be a relative, to sit in as his or her parent and receive or give whatever is required for the marriage. On rare occasions, some of the items (sometimes just a bottle of schnapps, a cloth and some money) given for the lady’s hand in marriage are packaged and given to somebody travelling home to give it to the family of the lady and explain everything to them. Finished!! In most cases, the man who is seeking such a lady’s hand in marriage eventually does not even know where she hails from nor do the actual family members know the man personally. Some Bulsa men are also guilty of this as many have married women from other tribes and have never bothered to bring such women home to know where they actually come from. Such men eventually die wherever they are and their children are lost to the family and tribe of the woman. This is quite dangerous because in the event of any problem occurring in the marriage, family members would not be there for such a person since they are not aware of such a union. There is also this unhealthy practice whereby young women are always eager to jump at an opportunity to marry men who are either in the city or abroad as a way of ensuring financial and social security for themselves and their families. Some parents, especially mothers, push their daughters into marrying rich and influential men because of the financial, social security and prestige benefits accruing from such unions regardless of whether the young girl would be happy in the union or not. Some young girls have even agreed to marry men merely by seeing their pictures which are posted to relatives at home. Eventually, the marriage rites are concluded by the relations without the family of the girl knowing the man and then the girl is ‘posted’ to her new husband whom she barely has known before. In the majority of cases, such marriages run into problems and collapse with resultant dire consequences on the unprepared young woman.

Another change in the process is the disregard for most of the taboos and values that come with the marriage process. Young men now “eat” the “forbidden fruit” several times and sometimes even impregnate or have a child or two with the young women before starting the process. Others have adopted the “tasting and dropping” method whereby they never initiate marriage rites for ladies they date but live with different young women in the form of concubinage; picking and dropping them at will without making efforts to marry any of them. Quite clearly then, the good morals and chastity that have to be strictly adhered to during courtship have long been thrown to the dogs and forgotten. It is also worthy of note that the taboo that forbid young suitors from marrying a young woman once they visit her paternal compound and see someone in the process of making Bulsa-kpaam (sheabutter) or tiak (mat of elephant grass) no longer means anything to young men and women of today. Thus, the majority of young men, especially the so-called educated ones, no longer believe in that and would still go ahead with the marriage rites even when they encounter such so-called bad luck related activities at the house of a would-be-bride on countless occasions.

New Marriage Forms

Here, I am talking about the introduction of western-style weddings and Islamic Awuriya or Amariya following the advent of foreign religions. I dare to say that the former is more predominant in our part of the world than the latter given the fact that there are more Bulsa Christians than Muslims. In particular, the advent of Christianity came with the demand for people who have become Christians to always do things in the ‘Christian way.’ This meant a particular marriage was not recognized until it was blessed in the church in line with the doctrines of that church. Over the years, it has become the vogue and the norm for a young girl or man to have his or her marriage blessed in the church with pump and pageantry as well as lavished banquets with every kind of food or drink available for patrons. The young woman being wedded, usually immaculately dressed in a white wedding gown that is either bought, sewn or borrowed, became the envy of all other single ladies who would do anything to be in the bride’s position!! Oh yes! Almost every single woman is now crazy to do a western style wedding in the church and wants it to be bigger than that of her colleagues’ even if the man is not ready. Some ladies, supported by their wealthy families, have even opted to foot most of the financial bill required for a wedding of the lady’s dreams. Others have pestered their men into borrowing just to foot the kind of lavish wedding that meets their lady’s taste. Even those who do not have cars, would often borrow or hire them for only the wedding ceremony and continue walking, riding or using the ‘trotro’ (public transport) afterwards. Interestingly, the increase in such western-style church weddings have become almost directly proportional to the number of divorces that emanates from such unions given that most of them are entered into out of monetary and social considerations other than love. Under such circumstances, the marriage is bound to run into problems and would not stand the test of time. Indeed, the upsurge in church weddings and craving for them by most young women or men have not only scared a lot of young men, who are not on sound financial footing, from contemplating marriage but has also led to the disregard for our traditional customary marriage practices and protocols among so-called Christian Bulsa. Indeed, some have even refused to engage in the customary marriage practices, regarding them as idol worship related practices, which are unchristian and should be avoided by so-called Christians. There are also instances where young Bulsa men and women residing in the south or in the diaspora refuse to come home with their partners to undertake the traditional marriage rites because of the fear of witchcraft or sorcery. The same can be said of the Islamic “Amariya”, though this is less of a worry since it mostly occurs among settler communities. The fact, however, remains that such foreign-style forms of marriage inevitably have a detrimental effect on Bulsa customary marriage practices since they are bound to erode such customary values and norms.

CONCLUSION

While it is good to embrace change, especially when the change is positive, we must balance the need for change with the need for preserving our cultural identity and the sanctity of our customary values and norms. As Bulsa, we must strive to preserve our customary values, norms and practices since they are indicative of who we are and what we stand for. There is therefore a need not to abandon our own customary marriage processes, norms and practices but to perpetuate them by adhering to them and also encouraging the young ones to embrace our way of life. Indeed, in line with the biblical adage ‘give to Caesar what belongs to him and to God what belongs to him’, it is still very possible to duly complete the traditional marriage rites and still go ahead to do your lavished church wedding. The other tribes like the Akan, Ewe, Ga, Dagomba, Frafra and Kassena do it, and why can’t we do the same? After all, many a pastor or priest would usually have asked to know whether you (as the groom) have fulfilled all necessary obligations required to lay claim to the lady as your wife before proceeding with the exchange of marriage vows. Therefore, it is incumbent on all of us, including the Bulsa in the diaspora to endeavour to observe our customary marriage practices and encourage our young ones to come back home with their partners to undergo the necessary rites based on the customs and traditions of our people. It is only when we do this that we would maintain our unique cultural identity and gain respect from people who marry our sons and daughters.